Breed to Succeed

A new plant finds its place in the market by changing something for the better, be it stronger, cheaper, or faster. Usually, the message focuses on some unique trait that sets it apart from the pack. However, even a great plant—one that redefines the category—can’t make a dent in the market without a volume supply chain. The reward for sweating the details is global sales, even for that sport found by the roadside.

Corporate teams are vertically integrated with their supply chains.

|

|

|

| Carnival Heucheras from Darwin |

Delta Pansies from Syngenta | Wave Petunias from PanAmerican |

Corporate Breeding Teams

SOME EXAMPLES: Darwin, Dummen, PanAmerican, Suntory, Syngenta, Proven Winners

Most teams exist to bring plant improvements to market in a structured manner. Modern series work underneath a corporate style of breeding guidelines with a group of checklists regulating plant selection within each genus. Details may change, but most majors work with groups, standards, and assumptions that form their corporate breeding style. Their focus starts with major crops like Delta, Caliente, Sombrero, SunPatiens, Vista, and Wave, then spreads out to hunt for competitive advantages.

A name and a spot on the product line are not guaranteed. Breeding teams find all manor of innovations, but sometimes genetics re-home themselves through partnerships. It happens regardless of the size of the agreement. “A corporation may have plants best marketed in another brand‘s product line,” said John Glados of Proven Winners. PW‘s full product line is built from four anchor teams but “we are constantly interacting with the large breeders and smaller breeders and independents.”

Since university and academia usually concentrate on foodstuffs, corporate teams also serve as a breeding ground for future breeders. “More often, they earn their stripes, then strike out on their own with private activies. Many independent breeders got started in corporate,” points out Karl Batschke of Darwin. Hires are exposed to fundamental technologies, key contacts, critical procedures, and important materials needed not only to breed, but to fulfill the market.

Employees also get a tour of genetic opportunities. Most breeders handle a range of plants, based on their blooming times. Petunias, with their rapid bloom-and-seed times and sheer volume, can keep a breeder busy, but not everything is a Petunia. More commonly, breeders are assigned several sets of genetics to explore.

Breeding houses work with and compete against established verticals.

|

|

|

| Kismet Echinaceas/Terra Nova | Colorblaze Coleus/U of Florida | Crazytunias/Westhoff |

Breeding Houses

SOME EXAMPLES: Chris Hansen, Garden Genetics, Intrinsic Gardens, Terra Nova, University of Florida, Westhoff

The shove and hustle of breeding opens the door for small and mid-sized firms to flourish either on their own or in partnership. Majors sometimes dip into the indie pool to find expertise they don't have in-house; sometimes an indie shepards its genetics to market. A breeding house brings tight focus, nimble speed, and an ability to explore aspects less explored. You might not know their source, but you might know products like Kismets, Chick Charms, ColorBlazes or Crazytunias. Often, the intuition of the chief (and sometimes only) breeder on the staff drives the agenda.

Due to septoria leaf spots, “we couldn‘t grow 'Goldsturm' even though it was a top-selling plant for us,” said Brent Horvath of Instrinsic Gardens. He gathered parents whose traits he admired and grew them in a field. “I let the bees do the moving of the pollen,” he stated. Notes kept in his head, Brent made selections quickly and regrew the candidates in larger batches. “I was the one making those decisions. I was the one searching, the one purchasing those plants so I knew what I had.”

An interesting aspect of most breeding houses is their companion business. Terra Nova’s liner trade informs their perennial breeding. Westhoff’s German retail sales network quickly winnows the *great* from the *meh*. Chicagoland Grows has its botanical garden parent. The companion business supports the breeding, but it‘s also a source of energy inside the breeding itself.

Their lightweight structure and focused view into the industry means the breeding houses often innovate quickly. “We are able to take more risks,” says Bart Hayes of Westhoff, a German breeder of annuals. “We can bring more unique products to market.” This is because of their point of view and a deep need to stand out from the majors. “At Westhoff, we have to come up with something other than a red Geranium. We are always looking for those alternatives.”

Foundlings in greenhouses has given the industry some popular standards.

|

|

|

| 'Fireworks'/Ron Strasko | 'Canary Wings'/Jared Hughes | 'Phenomenal'/Lloyd Travern |

Foundlings

SOME EXAMPLES: Pennisetum 'Fireworks' (Ron Strasko), Begonia 'Canary Wings' (Jared Hughes), Phlox 'Minnie Pearl' (Karen Partlow), Lavender 'Phenomenal' (Lloyd Traven)

Another path into the industry is through foundlings, stray events captured like lightning in a bottle by industry professionals. You have to be in the right place to spot one or the moment is washed downstream with the wholesale or retail shipments.

Pennisetum 'Fireworks' is an example of a foundling, discovered at Creek Hill Nursery in the grass house. “We made cuttings and rooted those,” said Ron Strasko. “From that, we sent it to TC and had them isolate it.” Cuttings from that master formed the basis of all future 'Fireworks' shipments.

Then there is Lavender 'Phenomenal', found in a dump pile behind a greenhouse. Lavenders are notoriously fickle, and this sport withstood all sorts of abuse. “If it could survive there, it could survive anywhere,” commented Lloyd Traven of PeaceTree Farms. A third example? Jared Hughes found a little green sport in a retail greenhouse where he worked. Eventually, after years of propagation and development, it became Begonia 'Canary Wings'.

Chris Hensen selects sharp, clean edges in his variegation and vibrant colors for his SunSparklers series of Sedums. No named variety overlaps another.

Development & Launch

EXAMPLES: Ball Ingenuity, Concept Plants, Plant Haven, Plants Nouveau

The development cycle starts once an ideal candidate is isolated and the decision is made to replicate it. If your ducks are not in a row at this point, don‘t move forward because the next phase is very demanding. In a corporate setting, breeding inherits the supply chain. For others, several firms focus on establishing strong supply chains.

“One of the biggest parts of our job is setting up the supply chain,” says Angela Palmer of Plants Nouveau. That chain consists of a complex set of tests for virus, selection, suitability, and a dozen other factors that affect the eventual path to successful replication. To keep those millions of inputs identical of time, additional selections are repeated as stewardship to keep the product features from drifting and picking up undesirable traits.

“You have to find people who understand how to handle those off-the-core materials,” says Joan Mazat, recently of Ball Ingenuity. “When a crop gets weird, it helps if they have an affinity for the material.”

Everyone calls for patience. Developing a good supply chain in two to three years is considered fast. Five to eight are more commonly cited, with some examples lasting past a decade.

Developing the supply chain is a new phenomenon. Twenty years ago it was common for production houses to maintain their own stock. It still happens in some places for very low volume stock, but the industry standard is to turn to the input.

All this preparation is important in order to stick the landing: CAST. The unofficial launchpoint of new varieties into the industry means bringing all the complex tasks together at one point on the calendar. “Launching late is not worth the effort,” said Bart Hayes. Joan Mazat agrees: “To trip and fall coming out of the gate, especially for a genus that isn‘t well-known, is bad. The product’s success is heavily weighted toward that first impression, so you need to check all the boxes beforehand.”

Kismet Echinaceas are bred from a core set of genetics with color variations expanded out.

Popular Articles

Trialing Edible Baskets

The Arthouse Expansion of Agastaches

Spotlight on Princettias

The Splitting of the Impatiens

Cartwheel Strawberry Twist Gerberas

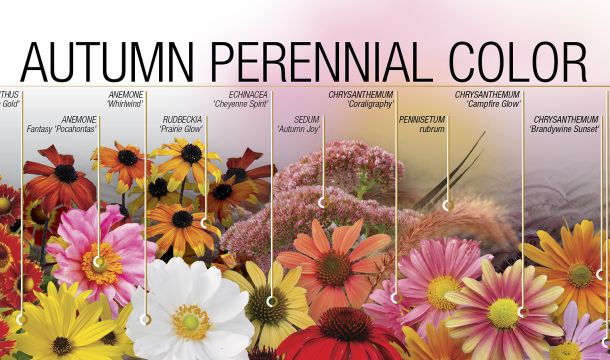

Autumn Perennial Color

Building a Patio Vegetable Program